The Menisci (singular form = meniscus) of the knee are crescent-shaped pads of tough, rubbery fibrocartilage, which is a tissue commonly referred to as "gristle" in the table meat processing industry. The paired menisci of the human knee are often simply referred to as the knee's "cartilages". They exist between the femur (thigh bone) and tibia ("shin bone") to cushion the knee joint during day-to-day use (see FIGURES 1a-1c). Their specific job is to spread out the joint's bone-to-bone contact pressure (caused by carrying your body weight) over a broad area. This avoids concentrated stress in any one spot, which can cause breakdown and deterioration (arthritis) of the articular (gliding surface) cartilage covering the ends of the femur and tibia. Several forms of meniscus damage and deterioration are known to occur, which for general convenience have traditionally been lumped together under the umbrella terms "meniscus tear" or "torn cartilage".

Just like the rest of our body parts, our menisci do age and ultimately degenerate. While they can be suddenly torn apart by a violent injury at any age, they typically become gradually weakened, worn and broken down by natural processes as we get older, at times causing symptoms while at other times not. The rearward (posterior) portions of the menisci seem to receive the great majority of stress, both in day-to-day life and in traumatic knee sprains, thus almost all surgical work ends up being done on the posterior two thirds of these structures. Tears of the frontal (anterior) portions of the menisci occur only with relative rarity. Because healthy menisci perform a useful function in the knee, when injured they should be repaired and preserved whenever possible and practical. Meniscus lesions are typically classified by orthopedic surgeons as being either "traumatic" or "degenerative" tears. Traumatic Meniscus TearsA meniscus that is forcefully pinched between the femur and tibia during a knee sprain injury may tear, even if it is strong, youthful and undegenerated. Such tears are called "traumatic" because they occur suddenly and because the meniscus would not have failed at that time were it not for the highly stressful knee sprain. With few exceptions, simultaneous weight-bearing and joint rotation (as are typically seen in a wrenching, sprain-type injury) are required to tear a meniscus, as without the former, no impingement ("pinching") forces are experienced by the meniscus.

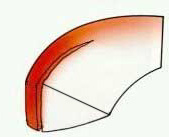

Only the outer (more peripheral) 30-40% of a meniscus actually has

a capillary blood supply (see FIGURE 2)

and thereby a significant potential for healing when injured. Sometimes

a traumatic tear will involve this peripheral, vascular (or so-called

"red") zone of the meniscus, whereas at other times it will

also (or only) involve the avascular (non-bleeding or so-called "white")

zone, which is in the inner 2/3 of the meniscus

(see FIGURE 3). Relatively vertical (straight split), traumatic

tears in the peripheral 1/3 of the meniscus have good healing potential,

thus are almost always surgically repairable. Tears in the inner, avascular

"white" zone of the meniscus do not bleed and are rarely good

candidates for surgical repair (at least with current technology), as

their healing potential is much more limited. Even if such tears seem

to heal initially, following a repair procedure, they have a fairly

high chance of breaking down again, thus requiring another surgical

procedure (meniscectomy) to excise them in the future.

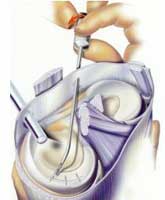

Degenerative Meniscus TearsIn the case of older, degenerated (weakened and worn) menisci that typically split apart or break down under routine, day-to-day or minimal stress conditions, the meniscus itself has not been healthy for some time. A degenerative meniscal defect will almost never bleed, and in fact may often occur gradually, without the patient even being aware of it! When such gradual, degenerative meniscal cleavage or fissuring develops and is discovered by MRI scanning or arthroscopy, while it is still commonly said that the patient "tore" their meniscus, this is actually a mischaracterization. To most people, "tearing" something implies a sudden structural failure in response to a specific, applied force. While the terms "torn" and "tear" are convenient for surgeons to use because they are familiar to patients, it is misleading to use them in relation to a degenerated meniscus that is simply worn, frayed, fissured, fragmented or just plain broken down. When a patient hears a surgeon say "You have torn your meniscus", they naturally infer that their meniscus was healthy and functioning properly before it "tore", and that like freshly torn ligaments, their "torn" meniscus can simply be repaired back together again or "fixed", neither of which is the case with degenerated menisci. Within the confines of currently available medical technology, degenerative meniscal defects are almost never amenable to repair. Degenerate menisci break down either spontaneously or under minimal stress because their intrinsic strength and toughness have already been compromised by way of the aging process and/or joint surface erosion caused by arthritis. Attempts at surgical repair are, therefore, pointless and usually doomed to failure. There is little to be gained by trying to stitch mushy, permanently weakened and improperly functioning meniscal tissue back together again. For lack of a better available treatment, surgical removal of the painful, defective meniscal tissue is usually the most appropriate course of action Degenerative meniscal defects can often be recognized by their appearance on an MRI scan and/or the circumstances under which the meniscus broke down (usually just routine daily "life" or during minimal stress, absent any genuine knee trauma). The age of the patient is also often a significant clue, as most degenerative tears occur in individuals over thirty. Many menisci were simply not genetically engineered to "go the distance", at least with respect to current human longevity. A thirty-year-old patient with a failed or failing meniscus may find the latter concept a bit difficult to accept, but from an evolutionary perspective, one must realize that for well over 99% of mankind's existence on this planet, the average human lifespan may have been 25 years or less due to the ravages of scarce food supply, a hostile environment and disease. There simply wasn't much point in nature developing menisci that lasted all that much beyond the age of thirty. The fact that some menisci last sixty or more years (mainly in people with "good genes" who do not let themselves get overweight) is actually what is biologically most remarkable! Treating Torn or Broken Down MenisciWhen meniscus repair is not possible or practical, surgically removing either acutely (freshly) torn or chronically broken-down meniscal tissue with an arthroscope usually provides satisfactory relief from the joint pain and locking / popping caused by the defective meniscus. Sometimes the pain relief is incomplete, however, since the knee has not really been structurally restored to normal and the joint surfaces themselves are subject to becoming tender (if they weren't already). Secondary measures may then need to be taken, in some cases including the surgical insertion of an allograft (transplanted replacement) meniscus into the knee joint. While meniscus transplants often prove helpful in relieving chronic pain in a non-arthritic knee that has lost a meniscus, it has not yet been proven that transplanted menisci prevent or reduce future knee arthritis in humans. For that reason, meniscus transplantation in a knee that seems to be doing fine despite having lost one of its menisci is controversial and only rarely done. When a previously healthy (non-degenerated) meniscus is traumatically

torn in a repairable (vascular) zone, repair methods may take

several forms. Sometimes very peripheral tears of the rear section of

the medial (inner side of the knee) meniscus are best repaired by way

of "open" (non-arthroscopic) surgery, using a skin incision

that can be kept as small as 1 1/4 inches in length. A secure and anatomically

accurate suture repair can be performed through such an incision. Most

other repairable meniscal tears are treated arthroscopically, using

guided meniscal suturing techniques (see FIGURE

4) or repair by way of bio-absorbable (slowly dissolving) meniscal

repair darts. In the latter case, a specialized insertion instrument

is utilized to pass the tiny fixation dart, pin or clip through the

inner section of the meniscus, across the tear and into the outer section

of the meniscus, thus holding both segments of the torn meniscus together

(see FIGURE 5).

The general internal environment of the knee at the time of repair seems to have some effect on the chance for successful meniscus healing after surgery. It has been found that meniscal repairs done at the same time as surgical reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament have a somewhat better chance of long-term success than meniscal repairs done by themselves. This may be due to biochemical healing factors that are more active within a knee joint that has been irritated in a more extreme fashion by way of more extensive injury and surgery. Aside from good surgical technique, the key to obtaining a high success rate with meniscal repair is often as simple as using selective judgment when making the decision to repair versus remove. All possible effort should be taken to repair otherwise healthy menisci that have excellent healing potential, whereas effort should not be wasted on thoroughly degenerated menisci that have no realistic chance of healing well and/or functioning normally. The decision whether or not to attempt repair in a "borderline" case (i.e., adequate healing is unlikely but not impossible) can involve some input from the patient, as well as consideration of the patient's specific circumstances. The younger the patient, the more consideration should be given toward meniscal repair, as loss of meniscal function sets in motion an accelerated aging process within the joint that leads to at least some degree of future osteoarthritis in the affected region of the knee. In an older individual (over 35 or 40) who is not overweight and who has no leg malalignment ("bowleg" or "knock-knee" deformity) a "borderline" meniscal tear with a sub-par chance for healing after meniscal repair is often best treated by primary meniscectomy. This is because the patient's knee has probably already been subjected to the majority of stresses that it will see during the course of its lifespan, and it has no specific risk factors (other than the meniscus injury) for premature osteoarthritis. This makes the loss of meniscal cushioning less objectionable. One must also consider the greater risk of surgical complications associated with meniscal repair procedures (vs. simpler and quicker removal procedures) and the extra surgical risks that the patient would be subjected to if a second procedure were to be required because the repair of a "borderline" tear ultimately failed. Even under ideal circumstances, a surgically "repaired" meniscus is not guaranteed to heal! When deciding whether to repair or remove problematic meniscus tissue, each patient's case must be considered individually, taking into account the patient's circumstances and wishes, the degree of pre-existing meniscal degeneration evident, and the overall physical condition of the knee at the time it is first inspected arthroscopically. Your surgeon's knowledge and expertise are also important!

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

FIGURE

1c - In this picture, the same knee anatomy specimen seen

in Figure 1-b is shown, but in a more normal anatomic configuration,

with the femur (above) resting upon the tibia (below). Here you

can easily see how the meniscus serves as a natural cushion or pad,

interposed between the femur and tibia. The arrows demonstrate the

direction of joint loading forces while standing. This specimen

also demonstrates nicely how the bones of the knee are lined with

articular (joint surface) cartilage (the white, border tissue coating

the spongy-appearing, dark red bone). Articular cartilage adds to

the shock-absorbing capability of the knee and provides the joint

with smooth, low-friction gliding surfaces.

FIGURE

1c - In this picture, the same knee anatomy specimen seen

in Figure 1-b is shown, but in a more normal anatomic configuration,

with the femur (above) resting upon the tibia (below). Here you

can easily see how the meniscus serves as a natural cushion or pad,

interposed between the femur and tibia. The arrows demonstrate the

direction of joint loading forces while standing. This specimen

also demonstrates nicely how the bones of the knee are lined with

articular (joint surface) cartilage (the white, border tissue coating

the spongy-appearing, dark red bone). Articular cartilage adds to

the shock-absorbing capability of the knee and provides the joint

with smooth, low-friction gliding surfaces.